Gottfried

Helnwein

Memorialising

the Holocaust

by Katy O'Donoghue, May 2008

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Monuments

- The

Warsaw Ghetto Monument

- Holocaust

Memorials

- Nazi

Monuments

Chapter 2: Counter-monuments

- The

Disappearing Monument

Chapter 3: Gottfried Helnwein

- Selektion (Ninth November Night)

- Kilkenny

Arts Festival

Chapter 4: Representing the Holocaust

Conclusion

Illustrations

Illus. 1: Epiphany 1 (The Adoration of the Magi), by Gottfried Helnwein, 756 cm x 2000 cm,

digital print, installation at Kilkenny Castle during the Kilkenny Arts

Festival, 2001.

Illus. 2: Heroes detail, Warsaw Ghetto

Monument, designed by Nathan Rapoport, Warsaw, Poland, 1948.

Illus. 3: Martyrs detail, Warsaw Ghetto

Monument, designed by Nathan Rapoport, Warsaw, Poland, 1948.

Illus. 4: Warsaw Ghetto Monument, designed

by Nathan Rapoport, Warsaw, Poland, 1948.

Illus. 5: Arno

Brecker, (1988) by Gottfried Helnwein, 99 x 66 cm, silver print.

Illus. 6: Harburg’s Monument Against Fascism, designed by Jochen Gerz and Esther

Shalev-Gerz, shortly after its unveiling in 1986, before its first sinking.

Illus. 7: Memorial graffiti on the Harburg Monument

against Fascism, designed by Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz, 1986.

Illus. 8: Harburg’s Monument Against Fascism, designed by Jochen Gerz and Esther

Shalev-Gerz, unveiled in 1986, almost gone.

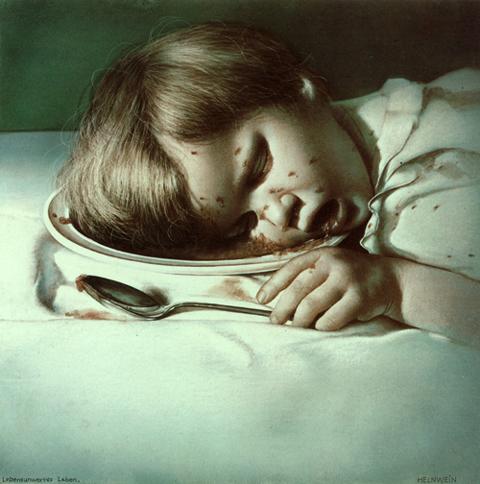

Illus. 9: Lebensunwertes Leben, (1979) by Gottfried Helnwein, watercolour on

cardboard.

Illus. 10: Selektion (Ninth November Night), by Gottfried Helnwein,

scanachrome on vinyl, installation, Cologne, Germany, 1988.

Illus. 11:

Selektion (Ninth November Night), by

Gottfried Helnwein, scanachrome on vinyl, installation, Cologne, Germany, 1988,

after vandalization.

Illus. 12: Epiphany I (Adoration of the Magi), (1996) by Gottfried Helnwein, oil

and acrylic on canvas, 210 x 333 cm, Denver Art Museum, Kent Logan Collection.

Illus. 13: Epiphany II (Adoration of the Shepherds), (1998) by Gottfried Helnwein, oil and acrylic

on canvas, 210 x 310 cm, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Illus. 14: Epiphany

III (Presentation at the Temple), (1998) by Gottfried Helnwein, oil and

acrylic on canvas, 210 x 310 cm, Jason Lee Collection, Los Angeles.

Illus. 15: Mary-Sheila

Walsh, Aoife Connelly and Eimear Connelly, by Gottfried Helnwein, digital

print, installation at Kilkenny Castle during the Kilkenny Arts Festival, 2001.

Illus. 16: Epiphany

III (Presentation at the Temple) by Gottfried Helnwein, 800 cm x 600 cm,

digital print, installation in Kilkenny city during the Kilkenny Arts Festival,

2001.

Introduction

Gottfried Helnwein has been described as an artist that has committed

himself to reminding the world of the Holocaust.[1]

Children are a recurring theme in his work; the strong/weak hierarchy makes

them a ready metaphor for the victims of evil. Stripped one by one of their

privileges, rights, sustenance, and finally their bodily integrity, the Nazi’s

victims were subjected to what Christopher Bollas has called ‘a radical and

catastrophic infantilization.’[2]

I first became aware of Helnwein’s work in 2001 when he exhibited at the

Kilkenny Arts Festival in Ireland. Large scale portraits of local children and

photographs of his paintings conflating Nazi and religious imagery were hung on

buildings around the city. I was particularly interested in the intense debate

that arose around the installation of the pictures. City Council members

objected to the hanging of work on City Hall, the public sent letters of

complaint to local newspapers and called in to the local radio station in

protest.[3]

During the exhibition two of the works were vandalised. Helnwein has maintained

that it is important to see a reaction to his work. In February I travelled to Bonn, Germany

and met with Helnwein to discuss how, through placing his work in the public realm, he attempts to keep

Holocaust memory alive by instigating a dialogue. His subject matter is

the repression of the greatest trauma of our century - National Socialism,

people’s complicity in it, and its consequences.[4]

Epiphany 1 (The Adoration of the

Magi) part of Gottfried Helnwein’s installation at Kilkenny

Castle

during

the Kilkenny Arts Festival, 2001.

Illus.

1

The Western tradition of memorial making has been founded upon an

assumption that material objects can act as analogues of human memory.[5]

It has been generally taken for granted that memories can be transferred to

solid material objects, which can come to stand for the memories, and by virtue

of their durability, preserve them beyond their purely mental and thus,

ephemeral existence.[6] I will

discuss the problems inherent in this conception of objects, and more

specifically monuments, as sites of memory using Nathan Rapoport’s Warsaw

Ghetto Monument as an example of a monument that has shifting meanings.[7]

In discussing the problems inherent in monuments I will highlight the

particular difficulties in constructing a monument to commemorate the Holocaust

and how this has resulted in new attempts to memorialise. I will discuss the

concept of the counter-monument with particular reference to Jochen and Esther Gerz’s

disappearing Monument Against Fascism,

War and Violence – and for Peace and Human Rights.[8]

Helnwein’s work has no illusions of monumental permanence but is often

monumental in scale and is very much sited in the public sphere. I will explore

how Helnwein’s work relates to the concept of the counter-monument and highlight

the similarities in the aims and objectives of his public memorials and Jochen and

Esther Gerz’s Monument Against Fascism.

I will discuss in detail Helnwein’s photo mural installations in the cities of

Cologne and Kilkenny and explore the supposed problems inherent in any

aesthetic representation of the Holocaust. I will consider the (later qualified

and amended ) quote by Theodor Adorno that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz in

barbaric’ and the subsequent debate among critics as to how an event such as

the Holocaust can or should be represented and what forms its images can or

ought to take.[9] In

conclusion, I will challenge the notion of there being any ‘limits’ to

representation with regard to Holocaust art.

Chapter 1

Monuments

Warsaw Ghetto Monument

Traditionally, the monument has been used as a site of memory; by its

seemingly land-anchored permanence, it might also guarantee the permanence of a

particular memory or idea attached to it.[10]

In this conception the monument would have to remain essentially impervious to

time and change. However, in his article ‘The Biography of a Memorial Icon’

James E. Young argues that monuments can, over time, accrue new meanings and

significance. Young discusses Nathan Rapoport’s Warsaw Ghetto Monument as an

example of a monument that has undergone many ‘personality’ changes.[11]

It was the first memorial to mark both the heroism of Jewish resistance to the

Nazis and the complete annihilation of the Jews in Warsaw and was unveiled on

19th April 1948 to mark the 5th anniversary of the Warsaw

Ghetto uprising.[12] The Warsaw

Ghetto was established in 1940 as a city based concentration camp and a transit

centre for Jews on their way to their death at Treblinka.[13]

Ten-foot-high walls topped with broken glass and barbed wire were erected

around what had been largely a Jewish slum section of Warsaw. On top of the

original 50,000 inhabitants, 500,000 Polish Jews were brought to the ghetto.[14]

Many died from starvation or disease before the Germans began rounding up the

remaining Jews for deportation to Treblinka. The Jewish Fighting Organisation was

set up to resist deportation; they forced the Nazis to withdraw from the ghetto

in a series of hit and run attacks that turned into full blown street battles

which raged for six weeks. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the first civilian armed

resistance in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II and although it was

unsuccessful, both the Jews and the non Jewish Poles of Warsaw celebrated the

significance of this event.[15]

Unlike other more abstract memorial forms such as the obelisk or the pantheon,

this free standing wall resembles a great tombstone, with wreaths of flowers

adorning its base. The seven heroically sculpted figures of men and women on

the monument’s western wall facing the open square are transformed to legendary

proportions.

Frontal

view of the Warsaw Ghetto Monument designed by Nathan Rapoport

Illus.

2

Except for one fallen youth at the lower right, the figures are rising

to resist and protect themselves. Each grasps a weapon of the sort found in the

ghetto: a muscular prophet figure on one knee picks up a rock; a young boy at

the left clutches a dagger; a young woman at the right holds a rifle; the

leader of the revolt, Mordechai Anielewicz holds a home-made grenade in his hand.

With his bare chest, tattered clothes and rolled up sleeves, clutching his

grenade almost like a hammer, Rapoport’s Anielewicz is unmistakably

proletarian.[16] On the

other side, in numerical reference to the tribes of Israel, twelve stooped and

huddled figures on the reverse embody archaic, archetypal Jews in exile. Eyes

to the ground, all trudge resignedly to their fate, except for the rabbi

holding a Torah scroll in one arm, who looks up and reaches to heaven as if to

beseech God. The monument’s dedication is inscribed in Hebrew, Yiddish and

Polish ‘To the Jewish People – Its Heroes and Its Martyrs’.[17]

Reverse

side of the Warsaw Ghetto Monument designed

by Nathan Rapoport

Illus.

3

As a Polish Jew in German occupied Poland, Rapoport fled to Russia. [18]

Although Russia was technically

allied with Nazi Germany at this point, her borders with Poland were open to

Jewish refugees who could either pay for sanctuary or provide skills and labour

deemed valuable by Stalin at the time. Rapoport spent several years working as

a state sculptor where he would set in bronze and stone all the forms and faces

designated worth remembering.[19]

His time working in Stalinist Russia no doubt resulted in the ultimate mixing

of Jewish and proletarian figures in the Warsaw Ghetto Monument.

The

Warsaw Ghetto Monument, designed by Nathan Rapoport

Illus.

4

Nathan Rapoport set out to make ‘a clearly national monument for the

Jews, not a Polish monument’.[20]

However, the monument has been revitalised by ceremonies conducted at its base

and with the state’s blessing it is now as much a gathering place for Polish

war veterans as for Jews. To the former Communist government’s consternation,

the Ghetto Monument’s square became a gathering place for Solidarity and other dissident

groups in the 1980s, who turned it into a performance space for protests.[21]

The government launched its own campaign to nationalise the monument after 1983

and square surrounding the Warsaw Ghetto Monument became both a dangerous and

necessary memorial space for the state, whose best interest ironically was to

preserve its literal reference to the Jewish uprising while assiduously

avoiding its symbolic reference to the current resistance.[22]

The American philanthropist and Warsaw survivor Leon Jolson commissioned

a reproduction of the monument from its original forms, with slight aesthetic

modifications, to be installed at Yad Vashem on Har Hazikaron (Remembrance

Hill) in Jerusalem.[23] The

decision to recast the Warsaw Ghetto Monument in Israel after 1967 came about partly

amid fears that its Jewish life in Poland could not be guaranteed. In being

left to stand in an environment both hostile to and bereft of Jews, the monument’s

Jewish significance and character now seemed threatened as never before. American

Jews and Israelis worried that, as Jews were being expelled from the party and

unions in Poland, Jewish meaning would be elided from the Warsaw Ghetto

Monument.[24]

Unlike its back to back setting in

Warsaw, at Yad Vashem the heroes and martyrs are placed side by side so they

may be viewed simultaneously. A handful of those involved in the Ghetto

uprising lived to fight in Israel’s own War of Independence. Israeli

independence followed the liberation of the camps by three years and was regarded

as an extension of the Jew’s struggle for survival in Europe.[25]

By uniting past heroism and resistance with present, the recasting of the

monument invites Israelis to remember parts of their own war experiences in the

images of the Ghetto Uprising.[26]

In Israel, therefore, this cannot be a memorial to victims so much as it is to

victory; it recalls the Jews’ ultimate triumph over the Nazis in their survival

and, in having risen at all, the Jews’ victory over their own past responses to

persecution.

Holocaust Memorials

Although the Ghetto Monument was intended by the artist to be ‘a clearly

national monument for the Jews, not a Polish monument’, it has since been

nationalised by Poland and Israel. [27] Monuments are open to appropriation and

can therefore, not always guarantee the permanence of any particular idea or

memory. Commemoration of the dead of the First World War was probably the

largest and most popular movement for the erection of public monuments ever

known to Western society.[28]

After 1918, there had followed a period of political turmoil, Germany had lost

the war and in an attempt to deal with their grief and bitterness there was a

gigantic, though decentralised and uncoordinated, programme of erecting war

memorials.[29]

When War broke out again in 1939, Germany was the country with the highest

number of memorials in the world.[30]

The purpose of nationalist war memorials and memorials such as the Warsaw

Ghetto Monument has traditionally been to commemorate resistance and to

transform traumatic individual deaths into acts of national celebration and

heroic assertions of collective value. [31]

A war memorial is successful when personal human sacrifice is justified for the

greater good. If the traditional aim of war memorials is to encourage the

resolution of suffering, and to validate the personal sacrifice by affirming that

‘they did not die in vain’ such cannot be said of Holocaust memorials, where

nobody can claim the deaths served any purpose whatsoever.[32]

Unlike state sponsored memorials built by victimised nations to themselves;

Holocaust memorials are necessarily those of former persecutors remembering

their victims.[33] The

difficulty in commemorating the Holocaust is that memory work that attempts to

deal with such an event must not be redemptive. The primary aim of Holocaust

memorials is to repudiate and lament, not affirm; both the historical realities

and the archaic values that seemed to have spawned them.

Nazi Monuments

Between the Nazi abhorrence of entartete

kunst or ‘degenerate art’ – and the officially sanctioned socialist

realism of the Soviet Union, the traditional figurative monument had enjoyed

something of a revival in totalitarian societies.[34]

Both regimes commissioned, or made possible, works of public art which would

reflect their ideals of pure Aryan race or workers solidarity. In its consort

with this century’s two giant totalitarian regimes, the monument’s credibility

as a public site of memory was thus eroded further still.[35]

In the 1980s and 90s Gottfried

Helnwein produced a series photographic portraits entitled Faces. The series was a collection of portraits of icons of

contemporary culture, both high and low, that he was particularly interested in

including: Mick Jagger, Michael Jackson, Andy Warhol and William S. Burroughs.[36]

Helnwein also wanted to take photographs of ‘the last witnesses who were close

to the center of power, which caused the catastrophe’.[37]

He photographed two leading artists responsible for the dominating aesthetics

of the Third Reich: Leni Riefenstahl, a film maker who had directed the great

propaganda spectacles of the Nazi party, and Arno Brecker, whose sculptures embodied

the Nazi ideals of pure Aryan race. Helnwein’s photograph of Brecker shows the

ageing sculptor with a suspicious expression. Helnwein reports that both Arno

Brecker and Leni Riefenstahl tried to justify their fascist activities to him

by claiming that they simply worked on commissions for the reigning powers and

had no political agenda of their own.[38]

Arno Brecker, (1988)

Illus.

5

Interestingly, when Nathan Rapoport began constructing his Warsaw Ghetto

Monument, he travelled to Sweden to source granite for the monument’s retaining

wall. The Jewish agency in Stockholm directed him to the best quarry in the

area, where he discovered a huge cache of perfectly cut Labradorite granite

blocks, ready to be shipped. He was informed that the blocks had been ordered

during the war by Arno Brecker for a monument in Berlin to commemorate Hitler’s

victory. Rapoport had the granite sent to Warsaw for the construction of the

Ghetto Monument.[39] In its use

of the giant proletarian figures of the Stalinist era and the typological image

of Jews in exile, the Ghetto Monument has found little critical consensus and

has been subsequently condemned by Post War critics as being too Stalinist and

not Jewish enough.[40]

Chapter 2

Counter-monuments

With the attempts to memorialise the Holocaust in Germany there was a

realisation that conventional memorial practices were inadequate and

inappropriate to the task. Pierre Nora has warned that rather than embodying

memory, the monument may displace it altogether, supplanting a community’s

memory-work with its own material form. ‘The less memory is experienced from

the inside,’ Nora cautions, ‘the more it exists only through its exterior

scaffolding and outward signs’.[41]

Thus, once we assign monumental form to memory, we may have to some degree

divested ourselves of the obligation to remember. In shouldering the

memory-work, monuments may only serve to relieve the viewers of their memory

burden.[42]

One of the contemporary results of Germany’s memorial conundrum is the rise of

its counter-monuments. In his essay The

Counter-Monument: Memory Against Itself in Germany, James E. Young

discusses how this genre of Holocaust anti-memorials has attempted to deal with

the danger that a monument may contribute less to memory than to forgetting.[43]

Counter-monuments are memorials conceived to challenge the very premise of the

monument. They involve the creation of self conscious memorial spaces where the

aim is not to embody the memory but give it back to the community, not to

console but to provoke, not to remain fixed but to change and to demand

interaction from the viewer.[44]

In their abstract form, these counter-monuments claim not to dictate a specific

object of memory. Rather, they more passively accommodate all memory and

response. By inviting viewers to commemorate themselves, the counter-monument

reminds them that to some extent all any monument can do is provide a trace of

its makers, not of the memory itself.[45]

The Disappearing

Monument

Berlin born conceptual artist Jochen Gerz was one of six artists invited

to propose a design for the city of Hamburg for a Monument Against Fascism, War, and Violence – and for Peace and

Human Rights.[46] He worked

together with his wife, Esther Shalev-Gerz, toward finding a form that

challenged the monument’s traditional illusions of permanence and its

authoritarian rigidity. The artists’ first concern was how to emplace such

memory without alleviating the need for individuals in the community to

remember. Their second concern was how to build an antifascist monument without

resorting to what they regarded as the fascist tendencies in all monuments.

‘What we did not want,’ Jochen Gerz declared, ‘was an enormous pedestal with

something on it presuming to tell people what they ought to think.’[47]

They decided that their monument against fascism was to be a self-abnegating

monument. It was a twelve-meter-high, one-meter-square pillar, made of hollow

aluminium and plated with a thin layer of soft, dark lead. They chose to place

it in the commercial centre of Harburg, a suburb of Hamburg and in their words

a ‘normal, uglyish place’. The monument stood in a busy thoroughfare outside a

shopping mall and was unveiled in 1986 with a temporary inscription at the base

that read in German, French, English, Russian, Hebrew, Arabic and Turkish:

We invite the citizens of

Harburg, and visitors to the town, to add their names here to ours. In doing

so, we commit ourselves to remain vigilant. As more and more names cover this

12 meter tall lead column, it will gradually be lowered into the ground. One

day it will have disappeared completely, and the site of the Harburg monument against

fascism will be empty. In the end, it is only we ourselves who can rise up

against injustice. [48]

A steel-pointed stylus, with which to score the soft lead, was attached

at each corner by a length of cable.[49]

The names were intended to be a visual echo of the war memorials of another

age, the black column of self-inscribed names might thus remind all visitors of

their own mortality. However, even the artists were taken aback by what they

found after a couple of months: an illegible scrawl of names scratched over

names, stars of David, funny faces and swastikas. People had come at night to

scrape over all the names, even to pry the lead plating off the base.[50]

However, when authorities had spoke to the artists about the possibility of

vandalism, Jochen and Esther Gerz had replied, ‘Why not give that phenomenon

free rein and allow the monument to document the social temperament in that way?’[51]

Harburg’s

Monument Against Fascism, designed by

Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz, shortly after its unveiling in 1986, before

its first sinking.

Illus.

6

Memorial

graffiti on Harburg’s Monument Against

Fascism

Illus.

7

As one and a half meter sections were covered with memorial graffiti,

the monument was lowered into the ground, into a chamber beneath that is as

deep as the column is tall. The faster visitors covered each section, the

faster it was lowered into the ground. After the final lowering in November

1993, nothing was left except the

top surface of the monument which was then covered with a burial stone

inscribed ‘Harburg’s Monument Against Fascism’[52] The intended effect was to have

returned the burden of memory to the public who had visited and signed the

monument. From the beginning, the artists have intended this monument to

torment, not reassure or redeem. They have likened it to a great black knife in

the back of Germany, slowly being plunged in, each thrust solemnly commemorated

by the community.[53]

Harburg’s

Monument Against Fascism, almost gone

Illus.

8

Jochen Gerz would like every memorial to return memory to those who came

looking for it but Young reminds us that these monuments are dependent on

public knowledge and when the monument disappears, there is a risk of

forgetting:

If we want [the next

generation] to look at the landscape, a landscape of invisible monuments will

also be one that demands people who know something. The question is if we will

always know enough to bring our memory and history back to these sites. [54]

While the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial has been accused of being too

proletarian, Rapoport has contested this view with a defence that highlights

one criticism of conceptual monuments:

Could I have made a stone with

a hole in it, and said, “Voila! The Greatness of the Jewish People?” No, I

needed to show the heroism, to illustrate it literally in figures everyone, not

just artists would respond to. This was to be a public monument after all. And

what do human beings respond to? Faces, figures, the human form. I did not want

to represent resistance in the abstract: it was not an abstract uprising. It

was real.[55]

The minimalist architecture of counter-memorials such as Jochen Gerz’s

disappearing monument have also aroused considerable controversy and

condemnation. Young explains popular resistance to these modernist memorials as

due to the inadequacy of these sites to gather together personal memories into

a collective space.[56]

Abstraction may frustrate the

memorial’s capacity as a locus for shared self-image and commonly held ideals.

In it’s hermetic and personal vision, abstraction encourages private visions in

viewers, which would defeat the communal and collective aims of public

memorials.[57]

Young argues that though it would seem the specificity of realistic

figuration would thwart multiple messages whilst abstract sculpture could

accommodate as many meanings as could be projected onto it. In fact, it is

almost always the figurative monument like the Warsaw Ghetto Monument that

serves as a point of departure for political performances. He says:

It is as if figurative

sculpture like this were needed to engage viewers with likenesses of people, to

evoke an empathic link between viewer and monument that might then be

marshalled into particular meaning.[58]

Chapter 3

Gottfried Helnwein

Austrian born Gottfried Helnwein has produced a number of large scale photo mural installations that invite comparisons with Gerz’s counter-monument. Helnwein, though, is dismissive of counter-monuments:

There is a big effort now with

holocaust memorials and holocaust museums and there are so many of them in

Germany now and I look at them and how they do it and I think many of them are

meant to also bury the past under all this stone and documentation. They are

also very similar and often they are so symbolic, just stones. They are too

conceptual, there is no emotion there. Just intellectual concepts, too minimalistic.

It is also a way of getting rid of guilt.…[My work] is a different type of

trying to force people not to forget or to look at something. To raise the

stuff that’s buried and meant to be forgotten. It is very different to making

now, decades later, some minamilistic stone monument. That is only to show that

the community is really doing something..[59]

He echoes the wishes of Jochen Gerz when he claims he wants his work to be not an answer but a question. [60] As Esther and Jochen Gerz intended their monument to be a knife in the back of Germany, Helnwein wants to employ his art ‘like a weapon, like a scalpel so that it touches the viewer.’[61]

Unlike Germany’s near obsession with its Nazi past, Austria’s post war

persona was constructed around the self-serving myth that they were Hitler’s

first victims.[62] Austrian

cooperation with Nazi Germany was swept under the carpet. In 1943, a carefully

worded statement was issued by American, Soviet and British foreign ministers,

in which Austria was openly declared ‘the first free country to fall victim to

Hitlerite aggression’.[63]

After the war ended, Austria quietly accepted the mantle of martyrdom and was

proclaimed ‘liberated’. A full scale de-Nazification program began which left

behind few tell-tale signs of the Nazi era. Germany’s painfully self-conscious

memorial culture contrasts with Austria’s general ambivalence towards the

recent past. Young points out that partly because of the confusion generated in

Austria by official memory, and partly because of a reluctance to face their

past, Austrians have generally been content to let the Germans do the memorial

“dirty work”.[64]

Helnwein was born in Vienna in 1948. He described post-war Austria as:

A really strange place…

everybody was serious and depressed…and the people were unable to say or talk

about what happened. Not because they were not willing but because of the

amnesia. In school we heard nothing about what happened, total denial, no

memory. The

only thing I heard was that we were the victim number one, we were the victims,

we were conquered; we had nothing to do with it.[65]

From 1965 to 1969 he studied at the Experimental Institute for Higher Graphic Education in Vienna.[66] During this time he decided, in protest against the conformist methods of teaching, to make a portrait of Adolf Hitler.[67] When his tutor saw it, he stormed from the classroom and returned with the school’s entire professional staff, including the director of the institute. The director gave a long winded exculpatory speech where he warned that ‘Whosoever recalls the accursed times of National Socialism is ruining the reputation of the Experimental Institute for Higher Graphic Education’, and the picture was confiscated. Helnwein describes this as:

The moment when I sensed for the first time: you can change

something with aesthetics, you can get things moving in a very subtle way, you

can get even the powerful and strong to slide and totter, anything actually, if

you know the weak points and tap at them ever so gently by aesthetic means. [68]

Having graduated from the Institute he refined his artistic strategy at the Vienna Academy of Arts, the same institute that Adolf Hitler was rejected from.[69]

For a class exhibition at the

Künstlerhaus in Vienna in 1971, Helnwin displayed the pastels of disfigured

children he had been working on alongside a new version of the notorious Hitler

picture. This time it was enclosed in a frame from the thirties which he had

acquired from an antique dealer. Reactions to the “Fuhrer picture” were mixed

– some viewers were appalled, while one man fell on his knees before the

painting revealing himself to be as fervent a Nazi as ever.[70]

In 1972 Helnwein held an exhibition

in the gallery of the House of the Press in Vienna, which was forced to close

after three days following massive protests by the employees and strike threats

by the workers council.[71]

During my interview with

Helnwein he recalled an encounter shortly after this exhibition closed with a

journalist from a conservative newspaper. The journalist told him he was

disturbed by the pictures he had seen and couldn’t sleep because he dreamt of

them. When Helnwein asked the journalist if he had been to war, seen real dead

bodies, or killed anyone, the journalist answered “yes of course, it was war.”

Helnwein then asked him “but as a news reporter don’t you get pictures of all

these horrible things, so bad that you can’t even print them?” and the reporter

said he did. Helnwein recalls that he found it really interesting that:

To see people dying, to see

pictures of actual dead and wounded was no problem and here we have a piece of

paper, with tiny little pieces of pigment on it, and that’s all it is really,

and that stopped him from sleeping, I don’t understand. I realised at that

moment that it is not my pictures, it’s the pictures that they have in the back

of their head that’s the problem. Usually they are dormant and asleep but with

art you can really break it out and that’s what they really hate.[72]

In 1979, spurred into action by an interview in an Austrian tabloid

in which the country's top court psychiatrist, Dr. Heinrich Gross, admitted

killing children at Vienna's Am

Spiegelgrund Paediatric Unit during the war by poisoning their food,

Helnwein painted Lebensunwertes Leben or Life is not Worth Living - a watercolour

of a little girl "asleep" on the table, her head in her plate.[73]

Lebensunwertes Leben,

1979, by Gottfried Helnwein

Illus.

9

Helnwein recalls:

He was the most celebrated

forensic psychiatrist and a member of the Social Democrats and he had all the

medals of honour that you could get and then they found out that he killed 800

children. So the reporter asked “did you poison them?” and [Dr.Gross] said they

were looking for a humane way [of killing them] so they came up with putting

poison in the food; so when the kids were eating they were not aware that they

would die. When I read [the article] I was in shock because somebody had just

admitted he had killed 800 children and everybody couldn’t be more relaxed. I

thought this should have raised a storm of protest or something but not one

voice, not one guy would write to this fucking newspaper, there was nothing. At

the same time on National Television for the first time, it was not an anchor

man but some guy in television was appearing with out a tie, like with a white

shirt but no tie. They got 3,500 letters of protest, they freaked out, people

were freaked, this is the end of everything, you know? They were completely

upset and I thought something is wrong. Here is a guy with no fucking tie and

people think it is the end. Here a guy killed 800 and it was nothing. And I

thought OK, maybe it is a reading problem, so I called the guys from the news

magazine and I said “Give me a page, I need a page, I will paint an open letter

to the guy.” And they said “Ok you can have it in two days” and so I had to

paint, day and night. I painted exactly what he said - the girl with the food

and her head in the plate. I painted it realistically with watercolours and then

I wrote this small thing thanking him and that actually caused a storm of

protest and so now suddenly people wrote to this magazine upset about the

painting, not about the guy. This tiny little picture started a huge

discussion.’[74]

Helnwein has always attempted to

make works that extend beyond the art scene into the social and political realm

and has embraced all the possibilities of technological processes to bring art

to the widest possible public. From 1966 he began to take his art out onto the

streets in a series of ‘aktions’ or

performances which were recorded and documented.[75]

In 1973 one of his pictures was used for the cover for Austrian news magazine ‘Profil’ and his earlier stated wish “to

be on all the magazine covers of the world” started to become a reality. The

German news magazines ‘Der Spiegel’

and ‘Stern’, the American ‘Time Magazine’, ‘L’Espresso’ from Italy, ‘Rolling Stone’ magazine and the German ‘Zeit Magazin’ all used work by Helnwein

on their covers.[76] In 2007 the

Virtual Museum of Art in the internet based world Second Life opened with a Helnwein retrospective.[77]

I hated the gallery system

anyway and I was always looking for a demographic form of mass

communication… I wanted to find

out how can you force people to look at something that they would rather not be

made to look at. I found that images can reach much deeper than words. [78]

The two installations I will

discuss continue this extension of Helnwein’s works into the public realm. Helnwein

produced large scale photo murals which were displayed in Cologne, Germany and

Kilkenny, Ireland. He confronts the passer by with images and thus attempts to begin

a dialogue, with a possible healing effect.

Selektion (Ninth November

Night)

In 1988 Helnwein planned a large installation to commemorate the fifty year anniversary of Kristallnacht entitled ‘Selektion (Ninth November Night)’. The installation consisted of a four-meter-high, hundred-meter-long picture wall with seventeen pictures of local children, running along the railway in a line between the Ludwig museum and the main train station in Cologne. [79]

When I did this memorial in

1988, it was the fifty year anniversary of Kristallnacht

and I thought Kristallnacht was

really a crucial point in time because it was the moment when suddenly the

Germans openly went against the Jews. Thousands of synagogues burnt down in one

night, all the businesses and stores were destroyed, they were chased in the

streets, the people were dead and that was open killing. There could be no

doubt for anybody, until then people said it was not that bad. For me, that was

the actual beginning of the Holocaust really…I shot all the faces of the

children then I put [them next to] this magic word Selektion which means selection; because that was what they were

doing. Selecting who should live and who should go to the gas chamber…I always

thought that when you look for the essence of this horrible nightmare then I

think its really the idea that a small group of people can decide and play God

and decide who has the right to live and who does not.[80]

However, he had difficulties finding a sponsor, as his planned installation of haunted children’s faces was unlike the muted, conceptualist Holocaust memorials usually commissioned by City Councils in Germany. The city of Cologne refused Helnwein permission to exhibit on city property.[81] In the end, he managed to get permission to use a site privately owned by the railway and had to realize the project at his own expense. Despite initial difficulties Helnwein was pleased with the result.

‘I thought, this is great

because now having them along the railway it makes even more sense. It was the

railways that deported them to the concentration camps.’[82]

Selektion (Ninth November Night)

installation in Cologne, Germany, 1988.

Illus.

10

The wall stretched from the Ludwig museum in Cologne to its main train station. It was in the city centre and a place through which thousands of people pass every day. [83] Each passer-by was confronted with larger-than-life children’s faces; painted white, they appear almost death like, lined up in a seemingly endless row as if for concentration camp selection. There was much media coverage of the installation and public debate ensued. After two days the installation was vandalised when someone slashed the throats of all the children on the panels.[84] Helnwein’s reaction to the vandalism of his work echoes Gerz’s wish to ‘document the social temperament’ with his disappearing monument:

Two days after they were hung

somebody cut all the throats and when I saw, I didn’t know what to do, it never

shocked me because I think if you show art in public places then the reaction

will be a part of whatever it will be, you cant control that. So then I decided

to just patch it up roughly and leave it and actually it makes the piece so

much more powerful. For me it was always an important part to see a reaction.[85]

Selektion (Ninth November Night) after

the installation was vandalized, Cologne, Germany, 1988.

Illus.

11

Like the concept of the

counter-monument discussed earlier, Helnwein’s murals create memorial spaces where the aim is not to

embody the memory but give it back to the community, not to console but to

provoke, not to remain fixed but to change and to demand interaction from the

viewer.

Kilkenny Arts Festival

For an exhibition of his works at the 2001 Kilkenny Arts festival in Ireland, Helnwein hung large photomurals of his paintings on buildings around the city. He included reproductions of his three Epiphanies that were created between 1996 and 1998. These works blend Nazi and religious imagery in a conflation of photography and painting.[86] In 1996, using a computer painting and ink jet method, Helnwein painted a series of Madonnas in which he adopted images of the Virgin and Child taken from well known paintings by Leonardo or Caravaggio and documentary photographs from the Nazi era and transferred them onto canvas. He then over-painted the image with oil and acrylic allowing the paint to subsume and become coexistent with the photograph. Helnwein’s Epiphany I (Adoration of the Magi) is a large (210 x 333 cm) painting in blue monochrome depicting the Adoration of the Magi. But the Madonna is a young Aryan maiden, and she presents a Christ Child who looks like a young Adolf Hitler. The wise men all wear SS and Reichswehr uniforms. They stand attentively, with approving respect, next to the Virgin. The most prominent Nazi holds a document in his hands, while the soldier on the right seems to examine the child, perhaps to see whether he is circumcised.[87]

Epiphany I (Adoration of the Magi) by Gottfried Helnwein, original painting, 1996.

Illus. 12

Epiphany II (Adoration of the Shepherds) again seamlessly melds a version of the Adoration of the Magi with a scenario from the Third Reich. The painting depicts a bare breasted Madonna-like mother with a child on her lap. The child points with closed eyes at the surrounding crowd of onlookers – some of them in Nazi uniforms. Once again the Madonna and Child take the place of Hitler in an old propaganda photograph.[88] Robert Flynn Johnson observes:

The apparent blasphemy of this scene of Nazi evil

encountering the Madonna and Child in a stadium setting is not so clear cut for

Helnwein. Rather it is a more symbolic case of unconditional evil, the Third

Reich, meeting "conditional evil", the Catholic Church, particularly

in light of Pope Pius XII’s alleged moral complicity during World War II.[89]

‘Epiphany II (Adoration of the

Shepherds)’ by Gottfried Helnwein, original painting, 1998.

Illus. 13

‘Epiphany III (Presentation in the Temple)’ is also based on a documentary photograph, this time featuring World War I British prisoners of war, disfigured by shell splinters. They are standing around a table on which a girl is lying, with the soldier on the far right paradoxically bearing Adolf Hitler’s features. Here the Presentation suggests a sacrifice; the iconography refers to the “anatomy lesson” which was a popular theme in 17th Century Dutch painting: a group portrait depicting scientists standing around a corpse or a skeleton.[90]

Epiphany III (Presentation in the Temple) by Gottfried Helnwein, original

painting, 1998.

Illus. 14

Helnwein supplemented the

reproductions of these existing paintings with a new set of works created specifically

for his installation at the Kilkenny Arts Festival. He made a series of portraits

of local children which echoes his earlier Selektion

(Ninth November Night)

installation in Cologne. Ninety children were photographed by the artist and

nine were displayed in central locations around the city, enlarged up to nine

meters high.[91]

Mary-Sheila Walsh, Aoife Connelly and Eimear Connelly by Gottfried Helnwein, 2001.

Illus. 15

Epiphany III (Presentation at the Temple) by Gottfried Helnwein, Installation

in Kilkenny City.

Illus. 16

I thought, a medieval city, it

would be great to make it a gallery and put the art on the streets. So people

that don’t even know about it will look at art and just walk through the

streets and be surprised. I also photographed children from Kilkenny and blew

them up and I wanted people to be involved in it. To be a part of the life, to

put it right in to the beautiful little city and I thought this is a Roman

Catholic country, Ireland. I expected there would be some reaction because of

the religious content.[92]

The installation in Kilkenny was also vandalized; Epiphany I (The Adoration of the Magi) was splashed with red paint and a photograph of a child was set alight.[93] A local newspaper The Kilkenny People reported that:

The images have been a major

talking point since before the festival began. A former mayor of the city, Mr

Paul Cuddihy, initially objected to a painting being hung on the City Hall for

fear it might be misinterpreted as lending support to Nazism.[94]

Members of the City Council were shown an image of Epiphany II and told an enlarged copy was to be displayed on the City Hall, although Helnwein had already decided to use another location. The debate over whether the images should be displayed caused the Kilkenny Arts Festival to issue a statement to the press explaining:

The subject matter of Helnwein's work are the often-difficult

subjects of prejudice, hatred and violence. Despite their difficult nature it

is important that these subjects are addressed and debate takes place regarding

issues like Nazi-ism, fascism and feelings of hatred towards immigrants and

minority groups. This is the subject matter of the work of Gottfried Helnwein

and the purpose is to promote public debate…In the Ireland of today where we

are faced with increasing incidents of hostility towards immigrant and minority

groups this is a legitimate subject for exploration through artistic work. It

is our belief that it is appropriate and reasonable to use public buildings to

exhibit art for general public display in a festival which is staged for the

enjoyment and stimulation of the people of Kilkenny and visitors to the city.[95]

Chapter 4

Representing the Holocaust

Helnwein’s work, and the controversy its hanging has caused, highlights

the problems inherent in Holocaust imagery. Ever since the Second World War

intellectuals have debated whether the Holocaust is at all representable. The

question is how an event such as the Holocaust can or should be represented and

what forms its images can or ought to take. This question raises two different

issues, how the Holocaust can be represented and how it should.[96] ‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is

barbaric’ wrote Theodor Adorno in 1949, in Cultural

Criticism and Society. [97]

This dictum has certainly played a powerful role in the ethical and aesthetic

debates surrounding aesthetic representations of the Holocaust. Adorno

subsequently qualified and amended this statement in his book Negative Dialectics;

‘Perennial suffering has as

much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have

been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.’[98]

Adorno’s statement has nevertheless come to function as a moral and

aesthetic dictate for the post-war era.[99]

The moral imperatives for ‘respectable’ Holocaust education and studies, as

dictated by Terrence Des Pres are:

1)

The Holocaust shall be represented,

in its totality, as a unique event, as a special case and a kingdom of its own,

above or below or apart from history.

2)

Representations of the Holocaust

shall be as accurate and faithful as possible to the facts and conditions of

the event, without change or manipulation for any reason – artistic

reasons included.

3)

The Holocaust shall be approached as

a solemn or even sacred event, with a seriousness admitting no response that

might obscure its enormity or dishonour its dead.[100]

Helnwein sets up an aesthetic

distance to the horror in his work by technically and electronically heavily

treating the images. With the aid of computer technology and multiple

reproductions he has endowed the documentary photographs of horribly maimed

faces in Epiphany III with an

alluring aesthetic gloss.[101]

One could argue that the

extermination of the Jews of Europe is as accessible to both representation and

interpretation as any other historical event. However, we are dealing with an

event which tests our traditional conceptual and representational categories

and Helnwein’s aestheticizing of the horror of

the Holocaust is morally contentious. Saul Friedlander in his book Probing

the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the Final Solution, describes the

Holocaust as an “event at the limits.” [102]

He explains that what turns the ‘Final Solution’ to an event at the limits is:

The very fact that it is the

most radical form of genocide encountered in history: the wilful, systematic,

industrially organised, largely successful attempt to exterminate an entire

human group within twentieth-century Western society. [103]

Berel Lang uses a similar notion of the limits of Holocaust

representation in the title of her book Holocaust

Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics, she

acknowledges that the phrase ‘art within the limits’ would be a provocation

even if the limits were left unspecified. Lang writes that Adorno’s assertion

of barbarism – not the impossibility, but the barbarism of writing lyric

poetry after Auschwitz – is one formulation of this perceived

representational limit. Although, she argues a justification might be argued

for barbarism against still greater barbarism – against denial for

example, or against forgetfulness. On this basis, Lang concedes that

representations may be warranted as within the limits, to serve a purpose in

calling attention to the historical occurrence itself.[104]

For a generation of artists and critics born after the Holocaust, the

experience of Nazi genocide is necessarily vicarious and hyper-mediated. They

haven’t experienced the Holocaust itself but only the event of its being passed

down to them. [105] The mass

appeal of National Socialism in Germany after 1933 was in a number of ways

obviously linked to aesthetic and artistic phenomena. Fascism could even be

defined as a form of government which depended on aestheticized politics,

featuring, for example, the marshalling of masses in geometrical formations and

the expression of party-political and governmental functions through uniforms,

insignia and ranking symbols.[106]

The aesthetics of political symbolism play a part in all systems of mass

politics, the difference in fascism is the frequency, intensity and

omnipresence of such practices. [107] Do works of art about the Holocaust tell

us more about the human experience under fascism or our potential to be drawn

to it? While most art work about the Holocaust carries an anti-war message,

some critics argue that it can implicate the viewer in a fascination with the

inevitably aestheticized representations of violence. Historian Omer Bartov,

for example, has expressed his sense of ‘unease’ with what he describes as the

‘cool aesthetic pleasure’ that derives from the more ‘highly stylized’ of

contemporary Holocaust representations.[108]

What troubles Bartov is the ways in which such art may draw on the very power

of Nazi imagery it seeks to expose. Susan Sontag inquired into this dilemma in

her essay Fascinating Fascism first

published in 1974. [109] She

expressed grave moral concern about the meanings inherent in, and audiences

served by, a spate of fascist aesthetics and Nazi imagery in contemporary

photography and film. Saul Friedlander raised the question again several years

ago in his own profound meditations on ‘fascinating fascism’, in which the

historian wonders whether a brazen new generation of artists bent on examining

their own obsession with Nazism adds to our understanding of the Third Reich or

only recapitulates a fatal attraction to it.[110]

While Helnwein’s use of Nazi imagery may seem offensive on the surface,

James E. Young suggests that the artist using Nazi imagery might ask:

Is it the Nazi imagery itself

that offends, or the artists aesthetic manipulations of such imagery? Does art

become a victim of the imagery it depicts? Or does it actually tap into and

thereby exploit the repugnant power of Nazi imagery as a way merely to shock

and move its viewers? Or is it both, and if so, can these artists have it both

ways? Where is the line between historical exhibition and sensationalist

exhibitionism? [111]

Although Helnwein argues that his intention is never to shock:

What is shocking?...Shock is

always the reaction of a society based on their belief system and their rules;

so the only thing a piece of art can do is touch or challenge some of the

arbitrary stupid rules. That’s why I

always like to quote Marcel Duchamp’s concept of art, art is the bipolar product,

it is 50% the artist and 50% the public, the onlooker, he said. And what

happens between these

two poles, something like electricity, that is art. That comes the closest to what I

think art should be, so what rules can you have? [112]

Conclusion

I asked how an event such as the Holocaust can or should be represented

and what forms its images can or ought to take. Holocaust art tends to be

unreflectively reduced by critics to how it can promote Holocaust education and

remembrance. In the context of Holocaust education and remembrance, historical

genres and discourses, such as the documentary, memoir or testimony might be

viewed as more effective and morally responsible in teaching the historical

events than more imaginative discourses. I have discussed the problems inherent

in monuments as sites of memory, both figurative and abstract, due to their

vulnerability to appropriation and multiple interpretations. Accordingly, Helnwein’s

work is also intrinsically problematic because it is imaginative not

documentary.[113] However, the

prospect of constraining freedom of expression would actually mirror fascist

politics. Critics agree that knowledge of the Holocaust is an important and a

desirable goal of public education (whether formal or informal). Thus, given

the diverse tastes and capacities of groups and individuals and the variety of

possible representations or images, there is really nothing more to be said, certainly

nothing to be criticised, no limits to be set or even hoped for in Holocaust

representation.

Bibliography

- City Council Resolution, Commemorating the 68th

Anniversary of Kristallnacht and recognizing the artistic contributions of

Gottfried Helnwein in keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive, Journal of the City Council of

Philadelphia, 2006. http://webapps.phila.gov/council/attachments/2911.pdf

- Bunbury, Alex “Artist’s Impression” Irish Tatler,

2002. http://www.gottfriedhelnwein.ie/country/ireland_special/artikel_893.html

- Forty

and Kuchler (eds.) The Art of

Forgetting, Oxford and New York: Berg, 1999.

- Apokalypse exhibition catalogue, Niederösterreichisches

Landesmuseum, Donaufestival, 1999.

- Helnwein exhibition

catalogue, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Konemann, 1999.

- Young,

James E. “The Biography of a Memorial Icon” in Representations No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and

Counter-Memory, (Spring, 1989)

- Young,

James E. The Texture of Memory:

Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, New Haven and London: Yale University

Press,1993.

- Young, James E At

Memory’s Edge: After Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and

Architecture, New Haven and London: Yale University Press: 2000.

- Bollas, Christopher Cracking Up: The Work of Unconscious Experience, London and

New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Adorno, Theodor “Cultural Criticism and Society” in Prisms translated by Samuel and

Sherry Weber, The MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusets, 1992.

- Adorno, Theodor, Negative

Dialectics E.B. Ashton, trans. Continuum: New York, 1973.

Š Lang, Berel Holocaust Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics,

The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 2000.

Š Lang,

Berel (ed.) Writing and the Holocaust,

Holmes and Meier: New York, 1988.

Š Sergiusz, Michalski Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage

1870-1997, Reaktion Books: London, 1998.

Š Taylor, Brandon and van der Will,

Wilfried (eds.) The Nazification of Art:

Art, Design, Music, Architecture and Film in the Third Reich The Winchester

Press: Winchester, Hampshire, 1990.

Š Michaud, Eric translated by Lloyd,

Janet The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany,

Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Š Nora, Pierre translated by Marc

Roudebush, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire”, Representations 26, Special Issue: Memory and

Counter-Memory, (Spring, 1989).

Š Gibson, Michael “Hamburg: Sinking

Feelings,” ARTnews 86 (Summer 1987)

Š Gordon,

Adi and Goldberg, Amos ‘Interview with Prof. James E. Young’ May 24 1998, Shoah

Resource Centre,

International School for Holocaust Studies: http://www1.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203852.pdf

Š Konno, Yuichi interview with Helnwein

in Yaso Magazine 6th September, 2003.

Š Author’s

interview with Gottfried Helnwein 10th February 2008 in Bonn,

Germany.

Š Connolly, Katie “Helnwein, the man

who used his own blood to paint Hitler” The Guardian, May 16th 2000.

Š Virtual Museum of Art: http://www.vmoa-online.de/cms/

Š Kilkenny Arts Festival exhibition

catalogue, 2001.

Š Chris Dooley article “Gardai

Investigate Kilkenny Art Attacks”, The Irish Times, August 18, 2001.

Š Kilkenny Arts Festival statement to

the press in an article by Sean Keane in Kilkenny People, 27 July 2001.

Š Saltzman, Lisa Anselm Kiefer and Art after Auschwitz, Cambridge University Press:

Cambridge, 1999.

Š Friedlander, Saul (ed.) in Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism

and the “Final Solution” Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard

University Press, 1992.

Š Friedlander, Saul Reflections of Nazism: An Essay on Kitsch

and Death, New York: Harper & Row, 1984.

Š Bartov,

Omer Murder in our Midst: The Holocaust,

Industrial Killing, and Representation, New York and Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1996.

Š Kleeblatt,

Norman L. (ed.) Mirroring Evil: Nazi

Imagery / Recent Art, New Brunswick,

New Jersey and London: Rutgers University

Press, 2002.

Š Interview

with Brendan Maher in Start magazine.